This article originally appeared on chatelaine.com.

Celebrities, executives and wealthy heiresses bought into Nxivm’s promise of expanded consciousness and female empowerment. Then came the sex slavery, brainwashing and blackmail. Inside an alleged cult for successful women.

Sarah Edmondson’s quarter-life crisis started out normally enough. In 2005, five years out of Concordia University’s theatre program, she was living in a basement apartment in Vancouver, pinching pennies and wondering whether her IMDb page would ever include more than beer commercials and bit parts. That summer, when a movie by her director boyfriend got accepted into a spirituality-themed film festival, Edmondson tagged along. It seemed like a good networking opportunity and the perfect antidote to her existential ennui.

At the festival, she met another director, Mark Vicente, and they bonded over their shared interest in art as a path to expanded consciousness. A self-described “seeker,” Edmondson had always been eager to connect to a greater purpose. She was setting intentions and eating quinoa long before such things became trappings of the New Age establishment. Vicente said he thought she would get a lot out of seminars that he had been taking through a humanitarian organization called Nxivm.

Open-minded and idealistic, Edmondson didn’t even Google the group before putting the $2,000 initiation fee on her credit card and making arrangements to attend her first set of Executive Success Programs (ESP) seminars at a Holiday Inn in Burnaby, B.C. ESP is the entry point to Nxivm (pronounced “nex-ee-um”), which was founded in 1998 in Albany, N.Y., by entrepreneur Keith Raniere, and nurse and unlicensed psychotherapist Nancy Salzman. Step one was five full-day seminars, during which new participants were encouraged to share their fears and insecurities. The objective, they were told, was to heal emotional trauma by taking personal responsibility. According to the Nxivm philosophy, there is no victimhood — only growth by upgrading one’s “belief system.”

After those first seminars, Edmondson felt clearer, lighter, happier about her relationships and more in touch with her goals. Finally, she saw herself heading in a positive direction. And so, like any satisfied customer, she signed up for more.

Over the next decade, Nxivm would transform Edmondson’s life, giving her glamorous and powerful new friends and that sense of purpose she had been looking for. But it would also suck her into a dark world of psychological and physical abuse.

That world was made public last March, when the FBI arrested Raniere, who was hiding out in a Puerto Vallarta villa, and exposed Nxivm as his alleged sex-slave cult. The story made headlines because, well, “sex-slave cult,” and also because Nxivm’s membership included the actors Allison Mack and Kristin Kreuk from Smallville, Grace Park from Hawaii Five-0 and Nicki Clyne from Battlestar Galactica. A month after Raniere’s arrest, the FBI brought in Mack, who they allege was his devoted lieutenant.

Raniere and Mack, along with Nancy Salzman and her daughter, Lauren Salzman, Seagram’s heiress Clare Bronfman and Nxivm bookkeeper Kathy Russell, have been charged by the New York Eastern District court with racketeering, forced labour conspiracy, sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit identity theft. The indictment also accuses them of recruiting and grooming sexual partners for Raniere. (All have pled not guilty, and none of the charges has been proven in court. Many former Nxivm members, including Kreuk, claim they weren’t participants in or aware of any criminal activity.)

The allegations against Nxivm’s leaders, as detailed in court filings, are more twisted than the creepiest season of American Horror Story, challenging our understanding of cults and the people who join them. That so many successful, smart and famous women could get caught up in Nxivm is part of what makes the story so compelling. Hadn’t they heard about the Manson Family murders and Jonestown massacre? Didn’t they know about mind control? How could anyone be so naive, so blind, so, well, stupid?

Edmondson is 41 years old and doll-like, with dark shoulder-length hair and a pale complexion. Looking back, she can see a lot of red flags along the path to indoctrination, but she also sees how, from that very first seminar in Burnaby, she bought into the principle on which much of the cult life is based: If you feel uncomfortable or want to bolt, that’s good news — that means it’s working.

Edmondson spent more than 12 years in Nxivm. During that time, she didn’t just belong; she thrived, forming a close circle of Nxivm friends and rising through the ranks to eventually earn the title of senior proctor. She met her future husband, actor Anthony Ames, during an early visit to Nxivm’s Albany headquarters. In 2009, she opened the group’s only Canadian branch with Vicente. It occupied 5,000 square feet in a downtown Vancouver office building and resembled a spa, with hardwood floors, soft lighting and orchids. Other key Nxivm hubs were in Los Angeles, Mexico City and Tacoma, Wash.

Nxivm had six main tiers, and as members moved up through the levels, they earned coloured sashes and stripes. “Similar to karate” is how the process was sometimes described to newbies. In fact, it was more like a pyramid scheme, with members required to recruit new members to rise through the ranks. At the top of the pyramid was Raniere, who wore an extra-long white sash to symbolize his status as a “perpetual student.”

Members referred to Raniere as “the Vanguard” and spoke of him as a mix of Gandhi, Einstein and a Titanic-era Leonardo DiCaprio. Raniere claims he’s a genius, with an IQ of 240 (typical geniuses score 140). He says he spoke in full sentences by age one and played concert-level piano by the time he was 12. Some more verifiable facts: He is 58 and was born in Brooklyn. Before Nxivm, he founded Consumer Buyline, a multi-level marketing company that prompted investigations in 20 states — in 1993, the New York attorney general described it as an alleged pyramid scheme. YouTube clips of Raniere’s Nxivm “revolutionary” teachings show a combination of cheesy affirmations and Ayn Rand lite. But to his students, he was a great philosopher, one of the smartest men alive and a celibate (or so they were told). In those early ESP sessions, his portrait hung on the wall of every classroom. His students were conditioned to revere him even before they met him — which most never did.

This is how an organization like Nxivm works: A lot of people (approximately 17,000 over its 20-year run) dabble, taking a handful of expensive courses and then continuing on with their lives. A much smaller number of true believers pay tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars and end up devoting their lives to the organization. It’s both an effective revenue strategy and an explanation for how alleged cults can hide in plain sight — most people who get involved go back out into the world with no knowledge of any bizarre practices.

By the time Edmondson travelled to Albany for her first face-to-face meeting with Raniere, she had already spent 16 days and $6,000 on an extended version of ESP. Upon arrival, she was told Raniere would only meet new students at late-night volleyball games, between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m., where members (mostly women) would vie for private time with the Vanguard between serves and spikes. At first, the peculiar timing struck Edmondson as ridiculous and inconvenient. She wasn’t going to go — she didn’t want to. But there was a voice in the back of her head asking her what she was running away from. Wasn’t she committed to her growth?

In Nxivm, demonstrating one’s commitment was a daily exercise. New members took on “persistencies” to build accountability — five minutes of push-ups or an hour of writing, for instance. Failure to meet those goals resulted in “penances” like dieting, doing planks in the middle of the night and taking cold showers. Initially, the experience is rewarding because you’re making strides toward whatever goal you came with. And then, slowly, that goal starts to fade into the background.

This is the sinister bait-and-switch of alleged cults like Nxivm, according to Stephen Kent, a professor at the University of Alberta whose research focuses on new and alternative religious movements. People get involved because they’re looking to improve some aspect of themselves, but the transformation isn’t what they bargained for. Anyone seeking individualism finds their own mind replaced by a group mentality, anyone who wants to work on relationships ends up isolated from the people who really care about them, and anyone who wants to improve their career prospects eventually finds themselves in a new line of work: the cult.

Every feel-good Nxivm ritual had an underlying and unstated objective. In those first ESP sessions, for example, where newbies stand onstage exorcising their deepest insecurities, the point was to establish a false intimacy while gathering personal information about members that could later be used for coercion and blackmail. Early on in many cult-like organizations, there’s a strategic offensive known as “love bombing,” in which the recruit is enveloped in affection and attention. This may be particularly effective because people often get involved with alleged cults during periods of situational vulnerability: a breakup, a move, a death, a new job or some other type of personal upheaval.

Nxivm could also be a lot of fun — like adult summer camp. Edmondson hosted beach barbecues for the Vancouver branch. There were board game nights, holiday parties and an a cappella group called Simply Human that would perform on college campuses (in advance of a recruiting blitz). The chance to hang out with celebrities was another key aspect of the Nxivm recruitment strategy. In addition to Mack and other actresses, Nxivm attracted the children of political and high-society dynasties, including Clare and Sara Bronfman. The sisters allegedly donated $65 million to Nxivm, and funded a 2009 visit from the Dalai Lama and a getaway to Sir Richard Branson’s private paradise, Necker Island. Edmondson once flew to Alaska on the Bronfmans’ private jet. The glamour and good times distracted members from noticing how a wedge was being driven between them and their friends and family.

The more Edmondson became involved with Nxivm, the more it fully consumed her life. Her relationship with her mom, who didn’t approve of the time she was devoting to Nxivm, became strained. She skipped her best friend’s wedding for V-Week, an annual celebration of Raniere’s birthday (that cost $2,000 to attend). Her own wedding to Ames was officiated by Lauren Salzman (her Nxivm bestie), with vows written by Raniere. Allison Mack performed a throaty rendition of U2’s “All I Want Is You.” Everything seemed wonderful — until it wasn’t.

The FBI alleges Allison Mack instructed a series of Nxivm women to have sex with Keith Raniere.

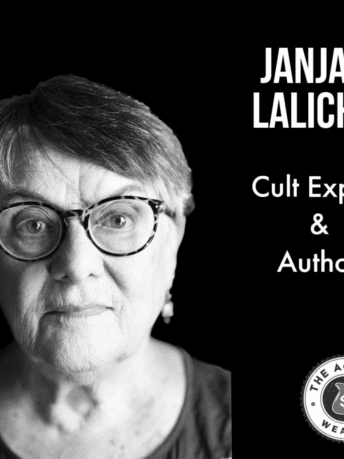

The FBI alleges Allison Mack instructed a series of Nxivm women to have sex with Keith Raniere.There isn’t much agreement between religious scholars and academics about the defining characteristics of a cult, except that all cults cut their members off from society and follow a charismatic leader. Another key commonality: “Nobody who gets involved in a cult thinks they’re joining a cult.” That’s according to Janja Lalich, an American sociologist who has spent 35 years researching cults and extremist groups, and counselled ex-members from organizations like the Children of God, the Unification Church and the Twelve Tribes. The idea that a person can be “too smart” to fall for a cult’s pitch is a persistent and inaccurate myth. In fact, says Lalich, it’s often the opposite: Intelligent people tend to share characteristics like curiosity and idealism that can make them more susceptible. “Cults aren’t looking for stupid people,” says Lalich. “They want individuals who can perform for them.” (Edmondson signed up 2,000 members for Nxivm over a decade.)

Lalich estimates that there are thousands of cults operating in North America. Some are religious and some are secular; some have a handful of members and some are thousands strong. Many look very little like that community of counterculturalists living out in the middle of the desert. These days, people become involved through seemingly innocuous entry points, such as work seminars and yoga retreats. Many alleged cults, including Nxivm, are structured around a large-group awareness training (LGAT) model, which is not all that different from what you might encounter at a Tony Robbins seminar or a celeb-branded wellness summit. “Cults have gone mainstream,” says Lalich. And by that, she means that cults have adapted to contemporary society and contemporary society has adopted certain cultish tendencies. In the 1960s, a typical cult might have promised enlightenment, revolution or an escape from “the man.” In the 1980s, cults espoused a Gordon Gekko–esque ideal of wealth and power. Nxivm attracted new recruits with a post-millennial cocktail of individualism, productivity and female empowerment.

Although both genders join cults, there are many aspects of contemporary cult culture that feel customized to fit women’s present wants and needs. Cults imitate the messaging of wellness brands like Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop, and wellness culture itself embraces some cult-like hallmarks. “Live your best life” may be an inspiring mantra, but it’s also a lot of pressure. Be happier! Make your own organic baby food! Form a meaningful relationship with a higher power! Of course, there’s a big difference between downloading a mindfulness app and joining a cult, but when you look at the way society is forever telling women that they need fixing and how today’s cults present themselves as the ultimate self-improvement solution, it’s easy to see why they may be preconditioned to drink the Kool-Aid. Or the green juice, as the case may be.

In January 2017, Lauren Salzman invited Edmondson to an elite group of Nxivm women called DOS. The abbreviation stood for Dominus Obsequious Sororium (loosely translated to “lord over the obedient female companions”), though Salzman didn’t mention that. Instead, she described the group to her as a female Freemasons and a “badass boot camp.” Its members, she said, would address significant world issues and influence elections (though any specifics around how this might actually work were never spelled out). When Salzman explained that Edmondson must call her “master” and she would refer to Edmondson as “slave,” she made it all sound like a silly, overly dramatic formality. She instructed Edmondson to hand over valuable or compromising collateral and framed it as an opportunity to demonstrate loyalty. Edmondson supplied a naked photo of herself and a written confession containing made-up allegations against her husband and parents. She would later demand the same of women she’d invite into the group.

DOS members would submit to “proof of readiness” exercises, in which a master would text one of her slaves in the middle of the night, and if that slave didn’t text back “ready” within one minute, the entire group would be reprimanded. Slaves demonstrated loyalty through “acts of denial,” like staying awake all night, being celibate and restricting themselves to a low-calorie diet. (Extreme diets are another significant manipulation tool. “When people are starving, their judgment is significantly impaired,” says Kent.)

In March 2017, Salzman escorted Edmondson to her DOS initiation in Albany. Edmondson, standing in the middle of a group of DOS members, followed instructions to take off her clothes and lie on a massage table. Three women held her down, and a fourth, a doctor, lowered a cauterizing iron onto the skin above her pubic bone, branding her with the DOS insignia. Some of the women in the room wore surgical masks to block the smell of burning flesh. “It was the most searing, awful pain,” Edmondson said in the CBC podcast Uncover: Escaping Nxivm. She wept through the entire ceremony, but she felt proud when it was done — like she had triumphed over her own weakness.

Two months later, Vicente visited Edmondson and shared some disturbing rumours he had heard about DOS. Over the course of their conversation, they came to realize the branding on Edmondson’s torso was actually a design that incorporated the initials of Raniere and Mack. After years of blind devotion, this was Edmondson’s breaking point. She told Ames that she wanted out of Nxivm. They planned her escape, packing up their Albany rental property before she fled on a train to Toronto.

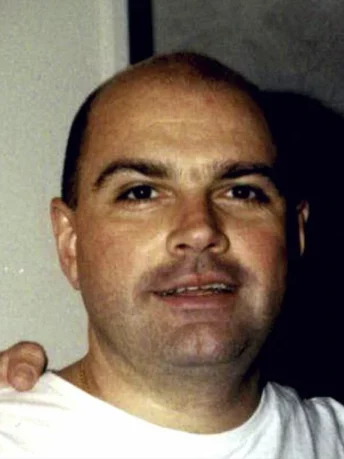

Keith Raniere, founder of Nxivm, entering a Dalai Lama event in downtown Albany in May, 2009. (Photo, Patrick Dodson)

Keith Raniere, founder of Nxivm, entering a Dalai Lama event in downtown Albany in May, 2009. (Photo, Patrick Dodson)Cult leaders are typically motivated by power, sex or money. Raniere appears to have wanted all three. Nxivm and DOS were cloaked in the language of female empowerment while working to oppress and exploit women. Patriarchal power structures and the sexual exploitation of women are common in cults. David Koresh, the leader of the Branch Davidians, forced his male followers to practise celibacy while he impregnated their wives and abused the children. In the Rajneesh movement (the cult explored in the Netflix series Wild Wild Country), the guru encouraged sterilization for male and female members. L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of the Church of Scientology, an alleged cult that also attracts well-known actors, once wrote, “A society in which women are taught anything but the management of a family, the care of men and the creation of the future generation is a society which is on its way out.”

The FBI claims that, despite his publicly professed celibacy, Raniere maintained a rotating harem of 15 to 20 women who were prohibited from talking about their relationship. His personal philosophies on gender were central to the Nxivm curriculum. In seminars, he explained how society perceived women as a bunch of weak, needy, flaky parasites and that empowerment could only be achieved by fighting back against this inherent female frailty. He would use the example of a woman cancelling an obligation because she had her period: “You don’t see men doing that.” One former member believes DOS was really just a way to marry his appetite for sex and power with the official program.

The FBI also alleges Raniere enforced restrictive dieting among his members (sometimes no more than 300 calories a day), in part because he prefers slender women. Most DOS members were thin and in their 20s and 30s. The two unnamed individuals at the centre of the FBI indictment say they were instructed to have sex with him by their master, who is believed to be Mack. Jane Doe #1 claims Raniere took her to an isolated cabin and commanded a second person (presumably another slave) to perform oral sex on her. Jane Doe #2 was instructed to “seduce” Raniere shortly before she escaped. Like many women involved in DOS, she feared her collateral would be released if she left. (But it was more than that: Lalich uses the term “bounded reality” to describe how members of alleged cults know the choices that will keep them in the leader’s good graces and feel they don’t have any options beyond that.)

Jennifer Kobelt, a Vancouver actor, alleges she was coerced by a fellow Nxivm member, an Albany doctor, into participating in a research study that included watching footage of women having their heads chopped off, the curb-stomping scene from American History X and the rape scene from The Accused. Terrorist groups train torturers using similar methods, which are designed to prepare members to commit and endure violence. “When you look at the things we hear about Nxivm — bullying, sexual intimidation, members harassing dissenters, women holding down other women — people can only survive those things if they are already desensitized,” says Kent.

Raniere is being represented by Marc Agnifilo, whose firm’s client list includes Harvey Weinstein, Martin Shkreli and Dominique Strauss-Kahn. In an interview with CBC, Agnifilo argued the allegations regarding coercive sex are false. The women in question, he says, were mature adults. “The government’s position has elements of sexism in it,” he said. On the specific matter of the brandings, he points to football players and fraternity members who have been known to partake in these rituals. “You know what the difference is?” he said in an interview with NBC’s Dateline. “They’re men.”

Lalich doesn’t believe it’s possible to voluntarily participate in something like a branding when under the influence of an organization like Nxivm. The person who would be doing the consenting, she argues, effectively doesn’t exist in that environment. Indoctrination initially involves a lot of peer pressure. “After a while, you don’t even need other people to berate you,” says Lalich. “You’re berating yourself because you’ve internalized the ideology of the group.” Even as she lay under the scalding-hot cauterizing iron, Edmondson was beating herself up. “Sarah, you said you were going to do this,” she told herself. “You’re looking for the back door, just like Keith says women do.”

It’s a state of mind Alexandra Amor can relate to: being so divorced from your own gut that it sounds like the enemy. Amor, who lives in Ucluelet, B.C., wasn’t in Nxivm, but between 1989 and 2000, she belonged to a cult based in Northern Alberta. It was small — just 30 people — and it didn’t have a name, which is not unusual. Amor got involved through meditation classes. At first, it was a way to make friends and connect with like-minded people. Slowly, she began to forgo outside relationships and found herself altered. “I treated people in the group the way the leader treated us: being extremely critical and shunning them if they didn’t follow orders,” she says. When she finally left, it was because the leader made her boyfriend break up with her in front of four members of the group. She only began to understand what she had been part of when she started to unpack her experience in therapy. Today, she says she is grateful and happy to be out, but there are still times when she experiences mixed feelings. “I equate it to an abusive relationship,” she says. “You can leave, and you can still have a lot of attachment.”

Many of the ways in which cults manipulate their followers mirror how abusive partners gain control over their victims. It’s an instructive comparison in terms of understanding not just why a person would stay in a cult but also how former members deal with the post-traumatic issues. In 2014, activist and abuse survivor Beverly Gooden started the #WhyIStayed movement as a way to push back against stereotypes around victims of domestic violence. Former cult members face similar stigmas and judgment.

Three women held Sarah Edmondson down on a table while a fourth branded her with a cauterizing iron. (Photo, Liz Rosa)

Three women held Sarah Edmondson down on a table while a fourth branded her with a cauterizing iron. (Photo, Liz Rosa)Edmondson’s departure from Nxivm and the media attention that followed Raniere’s arrest precipitated a large-scale exodus. Vicente left Nxivm around the same time. Edmondson has since faced harassment and accusations that she stole Nxivm secrets to start her own organization. In 2017, representatives of Nxivm filed a legal complaint against her with the Vancouver Police Department, claiming criminal mischief, but charges were never laid.

Edmondson is in therapy as she tries to figure out her life after Nxivm. She realizes there are people who view her as a villain in this story, and she feels a lot of remorse about the many people she recruited — some who remain in Nxivm or, at least, what’s left of it. Since the indictment, all of the centres have closed and programming is currently suspended.

Edmondson joined Nxivm to build confidence, tap into her potential and improve her career prospects. She’s getting back into acting and recently appeared in a Hallmark Christmas special, but if she is famous today, it’s as the woman who naively helped build an alleged sex cult.

Deemed a flight risk, Raniere is currently being held in jail in New York. The trials of Raniere and his co-defendants are set to begin this April. Unlike the other actors who have done everything possible to distance themselves from the Nxivm story, Mack has shown no sign of losing faith. She has even allegedly claimed responsibility for the branding idea. Of course, it’s possible she is acting in the best interest of her master. It’s hard to imagine how she might continue to justify her involvement, though the FBI indictment offers a chilling clue: When a prospective DOS recruit would express hesitation, the master would pause, look her straight in the eye and ask, “Aren’t all women a slave to something?”