From the Oakland Tribune

By Jill Tucker and Jason Dearen

Sunday, November 16, 2003

THE WHITEWASHED chair is empty.

Several bodies are face down on the floor in front of it, their arms wrapped around each other — a final attempt at comfort, frozen in death.

Hanging above, a wooden sign with stark white words deliver a pointed message:

“Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

This photograph is 25 years old, an indelible image from the Guyanan jungle that vividly documents Nov. 18, 1978, the day 913 people died from mass suicides and murders in a remote encampment called Jonestown.

Jonestown.

The word is enough to bring the memories flooding back.

Memories of the Rev. Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple. Of parents giving their children cyanide-laced punch before drinking from the poison-filled vats themselves. Of San Mateo Rep. Leo Ryan shot dead on an airstrip.

And of the seemingly endless bodies bloating in the jungle heat.

It is a past too painful to forget.

And yet there is the fear that remembering has not been enough.

Those with personal ties to this past and those who have studied it say society is still susceptible to another Jonestown.

They say there are lessons to be learned from the Peoples Temple tragedy — not just how cults or apocalyptic groups form or function, but how aggressive intervention by a perceived enemy can trigger or fuel violence.

They say these are lessons that can be applied to situations similar to Jonestown, to Waco or even to al-Qaida and the war on terrorism.

“Jonestown kind of inaugurated an era of apocalyptic terror,” said John Hall, a professor of sociology and director of the Center for History, Society and Culture at the University of California, Davis. “People who didn’t understand Jones- town took the wrong lessons when they went into Waco.”

Concern drove them

Jackie Speier didn’t want to go to Guyana, on the northern coast of South America, 25 years ago.

Official State Department briefings indicated nothing wrong at Jonestown. But her boss, Democratic Rep. Ryan, urged on by concerned relatives of Temple members, wanted to see for himself.

Speier sensed something would go horribly wrong.

Now a state senator, Speier said she ultimately overcame her sense of dread. She thought if she didn’t go, some might think women weren’t strong enough to play key roles on congressional staffs.

So she went — and barely survived.

The gunmen came suddenly out of the jungle on a flatbed truck, according to witnesses, ambushing the group standing on the airstrip waiting to board a plane back to Georgetown, the Guyanan capital.

Ryan, Speier and a group of journalists had just finished an overnight visit to Jonestown to investigate claims by a Bay Area opposition group that the cult was holding people against their will and subjecting them to violence.

When Ryan left, 16 Temple members went with him. Their defection apparently was the last straw for Jim Jones, who allegedly sent the gunmen to the airstrip before instructing his remaining followers to die.

At the airport, bullets pierced Ryan in the head and neck. He died next to the airplane. NBC reporter Don Harris, NBC cameraman Robert Brown, Temple defector Patricia Parks and San Francisco Examiner photographer Gregory Robinson were struck dead nearby.

Speier was shot as she played dead on the tarmac. Hours later, Guyanan troops rescued the survivors, many of whom had fled into the nearby jungle.

Could it happen again?

Her scars and an “Elect Leo J. Ryan” campaign memento on her office desk are reminders of that day — an event she believes could happen again.

“Jim Jones and the other cults that followed wrapped themselves around freedom of religion, and we are very loathe to take any actions against any, quote unquote, organized religions,” she said.

Yet even before Sept. 11, 2001, back to the new millennium in 2000, government officials and law enforcement have worked desperately to determine which new religious movements or cults were a threat to public safety or themselves and which were harmless, soul-searching sects.

“Of the nearly 1,000 cults operating in the United States, very few present credible threats for millennial violence,” the FBI wrote in a 1999 report. “Cults with an apocalyptic agenda, particularly those that appear ready to initiate rather than anticipate violent confrontations to bring about Armageddon or fulfill ‘prophecy’ present unique challenges to law enforcement officials.” The report continued, “Ascertaining the intentions of such cults is a daunting endeavor, particularly since the agenda or plan of a cult is often at the whim of its leader.”

In 1978, however, it appears federal officials or law enforcement had little knowledge of what was happening at Jonestown, of the suicide drills or the cache of weapons.

It was a group of Jones’ former followers along with worried family members — who comprised a group called the Concerned Relatives — that warned of the dangers.

Clearly, law enforcement and government officials today have a better understanding of the potential dangers associated with apocalyptic groups.

Yet academic experts say that understanding doesn’t necessarily translate into official actions that mitigate the potential for violence — whether dealing with the Peoples Temple, Branch Davidians or al-Qaida.

Often with apocalyptic groups it takes something to set them down the path of violence — a “them” in the us-vs.-them struggle. With 25 years of hindsight, these experts say it is important to question whether government actions ultimately triggered what would be the apocalypse for these groups.

Pushed into acting?

Would 913 members of the Peoples Temple have ingested poison if Ryan and a group of reporters hadn’t shown up in Guyana on Nov. 17, 1978, at the behest of the highly critical Concerned Relatives group?

Would 80 members of the Branch Davidian sect died in Waco, Texas, if federal agents hadn’t raided their compound with guns drawn? Likely not, Hall says.

“One thing that people in society at large need to recognize is that dealing with people in these groups is a very delicate matter,” he said.

While it’s hard to say what might have happened had Ryan’s group not demanded to visit Jonestown, what is clear is that external factors did have an impact on both the Peoples Temple and Branch Davidians — and currently plays into the war on terrorism.

“‘Before Jonestown and Waco, there was a sense that cults operated in a vacuum,” said Rebecca Moore, a San Diego State University religion professor who has studied new religious movements for the last decade.

Now, particularly after Waco, it became clear “that there are a lot of things happening on the outside that the group is responding to,” Moore said.

In the case of Jonestown, federal officials from Customs, Social Security, the Internal Revenue Service and other agencies were investigating the organization and individual members. News articles chronicled the fears of former Peoples Temple members. It was this public pressure that led Jones to relocate to the South American jungle.

While those stories and government investigations alone did not provoke the massacre, they likely gave credence to Jim Jones’ paranoid rantings and the supposed need for suicide drills.

“What we’ve learned in the intervening years and through academic study is that religious violence is interactive,” said Catherine Wessinger, a professor of religious studies at Loyola University in New Orleans.

“It’s not just these crazy people doing something violent.”

Most of those who died had decided they were willing to take their own lives rather than see their community destroyed, she said. Jim Jones Jr. was at a basketball tournament in Georgetown when his father, the founder of the Peoples Temple, told his followers back at Jonestown they had to die.

While his parents, friends and neighbors died, the then-teenager and his brother who was with him at the tournament lived. The Pacifica resident doesn’t want to dwell on the end of the Peoples Temple. Instead, Jones focuses on why a thousand people followed his father and took up residence in the hostile climate of Guyana.

They wanted racial and gender equality, Jones explained. They were political idealists who were hungry for his father’s utopian message.

“I don’t know if you could create a Jonestown now,” he said. “We’re 40 years out of the 1960s and people are not looking for a vessel to help their fellow man.”

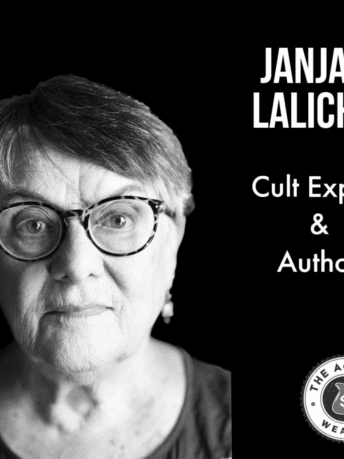

Indeed, Jonestown residents “were good people trying to create a better world,” said Janja Lalich, assistant professor of sociology at California State University, Chico.

“The idea was great,” she said. “I think we can also use it as a model for what not to do.”

The question then is what to do when a group appears to be violating the law or threatening public safety.

“If it’s suspected that a religious group is engaging in criminal behavior, then certainly it has to be investigated,” Wessinger said.

Yet it’s also important to study what they’re saying and what they believe.

“You want to communicate with them constructively and not make them feel like they’re boxed into a corner,” she said. “You need to go in with kid gloves and investigate very carefully.”

No more kid gloves

But in a post-Sept. 11 world, kid gloves and constructive communication aren’t part of the Patriot Act.

And for some, Jonestown and al-Qaida are two very different animals.

“I can say that I see no relationship between the reaction of nutty extremists who pose no threat to others, and the reactions of organizations formed to attack us,” Abraham Sofaer, senior fellow at Stanford University’s conservative Hoover Institution, said in an e-mail on the issue. “We need to indulge the former and destroy the latter.”

Yet others see parallels in the war on terror and what happened in Jonestown 25 years ago.

“What we’ve seen — and Jonestown was a harbinger for this — what we’ve seen since that time and especially with al-Qaida, is that religion is a powerful force for mobilizing people both for and against political initiatives,” said UC Davis professor Hall. “Religion is the wild card and it hasn’t found a very comfortable place in the deck.”

Both Jonestown and al-Qaida include apocalyptic messages — an us-vs.-them struggle in which the options are either prevail or die. To aggressively interact with or pursue such groups fuels the fire, academic experts say.

“It’s quite clear for al-Qaida it’s an apocalyptic struggle,” Hall said. “We have every interest in making them believe it isn’t apocalyptic.”

With Jonestown, the group was isolated in the Guyanan jungle, seemingly a non-threat to society at-large.

Al-Qaida is a much different story. Putting on those kid gloves to combat suicide bombers doesn’t seem realistic.

The question to ask, however, is whether reciprocal bombings create security or create more suicide terrorists.

“I’m all in favor of maintaining security and protection,” Loyola professor Wessinger said. “But bombing the heck out of people and putting pressure on them breeds more terrorists.”

Lessons of Jonestown

After Jonestown and the murder of her father on the Port Kaituma airstrip, one of Erin Ryan’s sisters joined a cult. Her other sister became the president of an anti-cult network.

Erin Ryan went to law school, then worked for the CIA and generally kept to herself about her father’s death. Until now.

She decided to speak out for the 25th anniversary because she wants a new generation of people to learn from the Jonestown tragedy.

She also wants to see more investigation, more attention focused on cults violating the law or threatening violence.

“Obviously, we’re a free and open society and people can believe and do whatever they want,” she said. “On the other hand, there’s a point at which state interest and safety come into play.”

She advocates a by-the-book look at such groups — focusing on greater scrutiny of tax and finance laws for religious groups.

“Religious deduction for taxes, Social Security fraud and welfare, that’s what we need to look at,” she said.

It is a less confrontational approach that can be applied to a Jonestown-like group or to the international stage to cut finan- cing to terrorists. In the meantime, Ryan said, she simply feels it’s important to remember what happened 25 years ago. Important to never repeat it.

“I feel there’s a whole generation who doesn’t know anything about it,” she said. “About what happened, why it happened and how it happened.”

Contact Jill Tucker at jtucker@angnewspapers.com and Jason Dearen at jdearen@angnewspapers.com . Staff writer Melissa Evans contributed to this story.